In the Summer of 2022, Catalystas embarked on a journey with ActionAid UK. We created a mapping research study that focused on work and rights issues affecting women in relation to their uses of digital platforms to acquire single-instance or temporary work (“gig” work). Our scope of focus included the sectors of Care and Domestic Services, Beauty Services, and Ride-Hailing and Delivery Services in three regions: Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Central and South America. The macro-perspectives of each region included recommendations tailored to each country’s context for Action Aid UK to consider in planning future interventions to support the rights of vulnerable women utilizing these emerging structures of work. Within each region, our research was further tailored to focus on ActionAid’s countries of operation, including Vietnam, Bangladesh, Uganda, Kenya, South Africa, Brazil, and Guatemala. Accordingly, Catalystas could zoom in and out, providing country, regional, and global insights and recommendations for ActionAid’s consideration.

Working with a team of six researchers, each fluent in at least one native language of a focus country as well as regional cultures, we utilized our networks and specialization in feminist research approaches together with our expertise in decent work standards to develop a strategic approach best suited to ActionAid’s needs and resources. We conducted the study in four phases: Inception, Desk Research, Primary Data Collection, and Analysis and Reporting. Throughout the process, we mapped over 700 unique data points across the three regions and nine focus countries via research conducted across multilingual media outlets and interviews with 25 subject matter experts representing industry, union and labor activists, and academics.

Our research found a troubling trend of an increase in violations of workers’ rights globally, resulting in an overall practical decrease in workers’ rights.

Despite varying degrees of legislative framework existing in some countries, workers’ rights are still being hindered in practice. We found that the deterioration of democratic practices, collective bargaining, and workers’ rights, coupled with the economic impacts of COVID-19 and the current global economic instability, has led to a more volatile and vulnerable work and social environment for workers – especially women. Our research also demonstrated the similarity across challenges faced by women working in the gig economy and informal markets.

These challenges, in particular safety and security for women, have been exacerbated by the anonymity of virtually-sourced labor. Additionally, despite the nature of digital work – particularly via social media platforms – when it comes to enabling women to conduct income-generating activities where they would otherwise be unable to work, gig-work has largely failed to support women in upward socio-economic mobility. Instead, in some cases it has even continued to reinforce cycles of poverty among vulnerable women due to the levels of income generation and the poor quality of labor standards and protections.

Due to the recent emergence of these sectors, still largely under-examined and unregulated, the data collection process proved challenging. Stakeholders in the sector across the study regions are still adjusting to new approaches and needs. Our team found limitations in knowledge, awareness, and focus on the issues surrounding app-based work acquisition and digital gig work among actors in each of our focus countries. At the finalization of our analysis and writing, Catalystas concluded that many of the challenges and barriers faced by women working in digital platforms and gig-work through applications are similar to that of the traditional markets. In some regions, there is still no regulatory framework to protect women in the workplace. In Africa, women face the highest levels of discrimination in terms of laws, social norms, and practices compared to women in other regions of the world.

There is also an overarching core challenge across the regions of our study: there is no effective legislative framework that adequately regulates the classification of digital workers. For instance, most of the countries that comprise this study have not ratified ILO’s Convention on Violence and Harassment (C190), with the exception of South Africa. As most platforms consider their workers as independent contractors instead of employees, they lack the rights, safety, decent pay, benefits, and protections they would be entitled to under traditional full employment contracts.

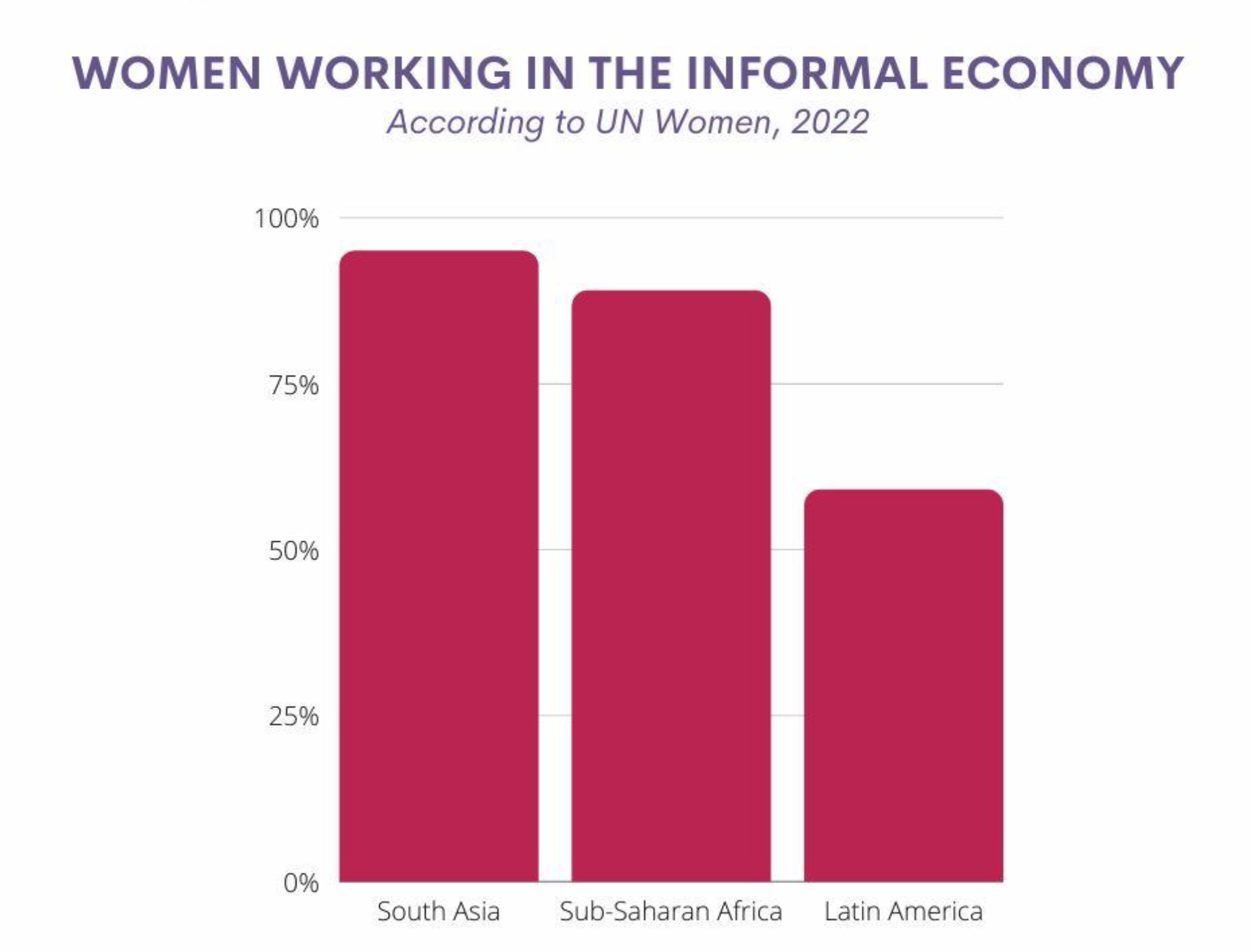

According to UN Women in 2022, women’s work remains predominantly in the informal economy.

In Kenya, for example, the informal sector amounted to 32% of the GDP, the ILO estimates that 88% of women work in the informal economy. In contrast, in South Africa, the informal trade sector – which is the largest informal sector – is made up of 47.6% women and 30.6% men. Latin America’s informal economy is composed mainly of women, young people, and lower social classes (indigenous and black populations, as well as the poor).

Access to work on digital platforms is fraught with biases and a lack of opportunities for women. In South Asia, there is a 19% point gap in ownership and a 36% point gap in mobile internet use between men and women. At the same time, Sub-Saharan Africa has one of the most significant gender gaps in mobile use worldwide (in 37 African countries, more than 50% of the population cannot afford 1GB of data per month).

One of the major barriers identified across all countries was the patriarchal social norms affecting all aspects of women’s lives, starting predominantly with their education and literacy. This remains, across the countries of this study, one of the highest hurdles for the most vulnerable and poverty-stricken women, as it prevents even accessing the digital job and sales market. Patriarchal norms also impact women’s access to financial capital and the internet (particularly via mobile phones), limiting their access to economic opportunities. For those who do access the digital gig-work economy, traditional patterns of gender-stereotypical labor are often repeated, with lesser access to training and education, access to decent-work overall, and socio-economic division-making power. Women working in lower-paid sectors such as care work, compared to higher-paid, male-dominated areas, such as cab driving. In such cases, digital gig-work has largely continued to reinforce gender norms rather than helping to break down gender barriers.

Our research shows that delivery and ride-hailing services dominate as the largest and most established app-based gig work across all regions, although these sectors are highly male-dominated. This is largely because the sector is deemed unsuitable and/or unsafe for women to work in, resulting in a low participation rate for women. Catalystas found that women dominate the labor force in the realm of beauty and domestic work (although it is frequently operated informally and through social media). However, the lack of legal protections combined with widespread violence against women has pushed women – especially indigenous and migrant women or women working in rural areas – to exclusion. In Guatemala, for example, we found through our discussions with stakeholders that the fear of harassment and abuse has led female gig workers in beauty services to only work with people they know directly or through trusted recommendations – limiting their earning potential. Our research found that most platforms offering opportunities for digital gig-work did not have policies or plans in place to support or address such identified concerns.

Given the limited protection for workers (or even the lack of, for digital gig workers) and the lack of a gender perspective when creating relevant legislation for their safety, it is not unexpected that trade unions and social movements are actively mobilizing for protests. Still, unionization and collective efforts in platform-acquired work structures are predominantly in the male-dominated driving and delivery service sector apps, leaving women once again out of the discussion. Limitations around union structures and processes go beyond just the exclusion of women; there is a lack of focus on digital gig work, as most of the countries in this study classify gig workers as self-employed or entrepreneurs, leaving them without enshrined legal employment rights and protections.

Labor unions in many of the study countries are also facing increases in pressure and attacks on their efforts to protect workers, severely limiting the space to expand efforts – Guatemala, for example, was named as one of the top ten worst countries to work in, according to the 2022 International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) Global Rights Index. However, with the right kinds of gendered and rights-based, and human-centered support, much progress can be made in overcoming these challenges and barriers.

Catalystas delivered our findings to ActionAid UK in an 85-page report with 14 matrices designed to enable ActionAid UK and its wider federation to make effective decisions on how to support the plight of female digital gig workers around the world.

Get in touch with our team for more information about digital gig work or other types of unique trailblazing research needs your company or organization may have.

Catalystas Consulting, Lange Voorhout 43, 2514 EC Den Haag, The Netherlands

© Catalystas Consulting. All rights reserved. Privacy and Policy

An Iranian-American with more than ten years of experience in international relations, economic development, and political empowerment, Beatrice is heavily invested in making the world a better place. Her work spans multiple regions of the world, often including high-risk environments, and her clients include non-governmental organizations, governmental bodies, and small-to-medium–sized corporations throughout the US, EU, Middle East, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Originally focused on the areas of economic development, security, and disarmament, Beatrice turned to the humanitarian field, where she has expanded her expertise to include international security policy, gender equality, and innovation planning. She is a highly skilled grant writer, program designer, auditor, and capacity and impact assessor, as well as an authority on client and donor relations and ethical corporate engagement strategy.

Her personal and professional interests come together in the use of technology and data to provide solutions and insight into human rights, higher education, sexual reproductive rights, and environmental preservation.

We built Lysta as an answer to one of our own problems: the need to quickly assemble teams of experts across various subject matter, geographic, linguistic, and thematic areas for projects and proposals as they arise. We quickly realized that we were not the only ones facing this challenge! With the speed that development projects require hiring, turnaround, and technical insights, we see first hand how helpful it is to have a ready-made database of vetted experts to call on.

For existing and potential Clients, you can access all consultant full profiles by signing up here as a client for free.

For consultants, adding your profile to Lysta means jumping to the top of the list for our clients in recruitment processes. We do the heavy lifting: the CV reviews, interviews, vetting, and personnel management; so when our clients come to us, they know they’re hiring someone they can trust to deliver high quality, timely results. Click here to add your profile for review.

We’re proud to be a link in the chain that connects the best of the best – don’t hesitate to reach out and see how you can put Lysta to work for you!